In this section we will look at the biology of Opabinia, focusing on its mode of life. Opabinia was a very peculiar animal by today’s standards and had a bizarre body plan. There has been much debate about how it used its body, since it was discovered in 1912 (Royal Ontario Museum, 2011). Opabinia regalis lived 505 million years ago near the end of the Cambrian Explosion, a time when the evolution of animals on earth was accelerated. The species lived through what may have been the most important evolutionary event in the history of life on Earth (Royal Ontario Museum, 2011), and for this reason we can learn a lot from its biology.

Jean-Bernard Caron Opabinia regalis. Complete specimen preserved laterally showing the proboscis, mouth and gut, four of the five eyes and lateral lobes. Specimen length = 72 mm.

Jean-Bernard Caron Opabinia regalis. Complete specimen preserved laterally showing the proboscis, mouth and gut, four of the five eyes and lateral lobes. Specimen length = 72 mm.

Opabinia had five eyes on stalks, and a long hose like structure extending from its head. Its body was divided into 15 segments with a pair of lateral lobes on each segment. It had a v shaped tail fin of three lobes on each side pointing upward (Whittington, 1975). It was a small animal, only 4 – 7 cm in length (Prehistoric Wildlife, 2011). Opabinia was benthonic in habitat, living on the sea bottom, (Whittington, 1975) and is assumed to have been a swimmer (Prehistoric Wildlife, 2011, Royal Ontario Museum, 2011). It would have propelled its body through the water by wave like motions of the lateral lobes (Whittington, 1975). It had gills on its lobes which would have been aerated as it swam.

Hutchinson (1930), Fossil of Opabinia regalis clearly showing the long flexible proboscis.

The hose like structure on the front of Opabinia’s body, extending from its head, is another unusual feature. This proboscis was flexible with a claw like structure containing spines on the end (Whittington, 1975). It would have been used to sift through the sediment and probe for food. Opabinia may well have been a carnivore as it is found in much fewer numbers than other animals in the same location from the same time (Prehistoric Wildlife, 2011). As a predator the proboscis would have been very useful for finding prey such as worms in the mud and in small crevices.

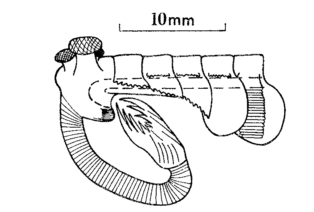

When it caught its prey Opabinia used its long flexible proboscis to pass the food item to its backward facing mouth on the underside of its body (Prehistoric Wildlife, 2011). The alimentary canal is U-shaped due to the backward facing nature of the mouth (Whittington, 1975).

Opabinia regalis Walcott (1912). Showing the U-shaped gut and backward facing mouth.

Opabinia regalis Walcott (1912). Showing the U-shaped gut and backward facing mouth.

Artists impression of Opabinia regalis catching prey item, Western Carolina University.

Artists impression of Opabinia regalis catching prey item, Western Carolina University.

Opabinia’s five eyes are another fascinating feature of its biology. There were two pairs of eyes on stalks and a central eye which was not stalked (Brysse, 2008). The eyes pointed up in slightly different directions and would have been capable of detecting changes in light intensity above and beside the animal, which would have aided in predator avoidance (Whittington, 1975). The eyes were most likely not compound as complex eyes are not known to have evolved by this time (Prehistoric Wildlife, 2011) but five basic photoreceptors working together may have had the same effect as the lens of a compound eye.

During the Cambrian Explosion, as biology evolved, Opabinia was part of the “Trial-and-Error Experiment of Animal Evolution” (Maruyama et al. 2014). It represents a transitional morphological position between several living phyla, but does not fit into any present-day phyla (Millwe, 2013). Some of the more unusual features of this enigmatic creature were not passed down through time, but it is believed to represent one of the most primitive species in the evolution of arthropods, which are now the most diverse and successful group of animals on earth.

REFERENCES:

- Brysse, K. (2008) ‘From weird wonders to stem lineages: the second reclassification of the Burgess Shale fauna’. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences, 39(3):298-313.

- Maruyama, S. Sawaki, Y. Ebisuzaki, T. Ikoma, M. Omori, S. Komabayashi, T. (2014) ‘Initiation of leaking Earth: An ultimate trigger of the Cambrian explosion’. Gondwana Research, 25(3):910-944.

- Millwe, K.B. (2013) The Precambrian to Cambrian Fossil Record and Transitional Forms. Available at: http://www.asa3.org/ASA/PSCF/1997/PSCF12-97Miller2.html.ori. (Accessed: 04 March 2014).

- Prehistoric Wildlife. (2011) Prehistoric Wildlife- Opabinia. Available at: http://www.prehistoric-wildlife.com/species/o/opabinia.html. (Accessed: 04 March 2014).

- Royal Ontario Museum. (2011) Royal Ontario Museum- Opabinia regalis – classifying the bizarre creatures found in the Burgess Shale. Available at: http://www.museevirtuel-virtualmuseum.ca/edu/ViewLoitLo.do%3Bjsessionid=3CE753FC5CCF0066830D54719541A931?method=preview&lang=EN&id=19489. (Accessed: 04 March 2014).

- Whittington, H.B. (1975) ‘The Enigmatic Animal Opabinia regalis, Middle Cambrian, Burgess Shale, British Columbia’. Philosophical Transects of the Royal Society of London Biological Sciences, 271(910):1-43.